What does our posture towards children in Church communicate? I’ve been thinking about this since we first came to our new Church in Clapham. In my experience, Orthodox churches afford a level of dignity and participation to children that I have never seen in protestant gatherings. My heart has softened to how important children are and how central their worship is. There is no age of reasonability; you do not need to pass a test to participate fully in the life of the church.

I have heard many in my previous churches dismiss Jesus’ childhood in an offhanded manner. I remember so clearly hearing a man who is now a Baptist pastor in Australia say around Christmas time ‘thank God Jesus grew up’. The implication was very strong, you couldn’t fail to miss it: why are we focused on the infant Jesus when what matters is what he did in adulthood? I too believed this, but have had my heart softened since attending my Orthodox church. The way my church treats children is, I think, a pure demonstration of the Gospel in action.

The light of the world

The first Sunday we attended St Peter and St Paul, a young girl no more than 6 or 7, was serving at the front of church. She was tasked with leading the procession of the Gospel, which meant carrying a candle sitting atop a tall brass candlestick. She led the way for another acolyte and the priest, who held aloft a bound copy of the Four Gospels. This role struck me as particularly dignified for a little girl, and her face was serene despite the heft of the candle. When the candle stick came to rest on the floor, it was so tall, the flame flickered above her hair. There she was, in a place of dignity, carrying a light to the world, participating in the life of a church in a way I’d never seen before.

A prayer for someone

Not long after the Bible reading, a young father brought his son, probably three years old, to the front of the church, to light a candle. Orthodox believers do this to represent a prayer, often for someone not present at church. You can put them in sand candelabras: a basin of sand for the candle to stand in. In our church, there are children-sized ones, not 45cm from the ground. The little boy was completely in his element. His dad stood back to let him figure out the sand and the flames and the candles. He swung the candle up and touched its tip to another, already burning, candle. He then swung his hand back around to attempt sticking it in the sand. His dad stepped forward to help him with this part, but it struck me how much trust there was between generations. This little boy was as able to lift up this symbol of prayer and take his place in the heart of worship.

A new covenant

Not long after, this same little boy, with all the bravery and gumption of a three year old, was first in line to receive the Eucharist. In the Orthodox tradition, taking the body and blood of Jesus means something much deeper than the mere symbolic communion of the protestant tradition. It is not purely psychological, a simple case of remembering Christ’s sacrifice. The Church does not explain exactly what is going on with the Elements, it is a Divine Mystery, but Christ is present in them.

With all this in mind, it was astonishing to see this young boy’s dad lift him to the common cup. The priest blessed this three year old boy the same as he blessed the older woman leading the choir, the same as the assistant priest, the same as me. He welcomed into his little body the Divine mystery that Christians have been performing for two thousand years.

A clear contrast

In my experience, protestant churches don’t hit on this important part of intergenerational worship, and they’re the poorer for that. In my previous churches, children were taken away into a side room, to hear Bible stories in a child-like (if not childish) way. They drew pictures and their cries of delight (and perhaps a few tantrums) could almost never be heard in the main congregation. We adored kids but didn’t see them as an integral part of the service. My suspicion is that protestants do this because in those services, the sermon is the heart of the service, not the sacraments. The focus on the verbal, dialectical worship means you essentially block out young children (not to mention people with mental or verbal processing challenges).

This of course goes much deeper and touches on the root of an inflamed nerve: do we baptise children? For my part, I disavowed my own infant baptism so much that I performed another one when I was 21, with a pentacostal gathering. For most if not all of my adult life, I rejected my entrance into the church as a child.

It has only been recently that I learnt how the Church treated children in the first two centuries of its existence. Something I love thinking about is Pliny the Younger, with all the Roman amazement you can conjure, describing how children belong to the ‘Christian cult’ in just the same way as the adults do. Respect for children once differentiated Christianity from the pagans. Saint Polycarp, bishop of ancient Smyrna and martyr of the faith described himself as having been in devoted service to Christ for 86 years in a manner that would clearly indicate a childhood baptism. Saint Irenaeus of Lyon wrote about “all who are born again in God, the infants, and the small children . . . and the mature.” This is to say nothing of the scriptural precedent: Christ welcoming the children into His Kingdom, the apostles baptising households and all their members (Acts 16:15, 16:33, 18:8; 1 Corinthians 1:16). The Christian church has been radically generational and I want to be a part of one that welcomes children into the heart of Christ’s kingdom: prayer, worship, the sacraments. I want to be a part of a Church that dignified childhood the way Christianity has always done.

A note on the Incarnation

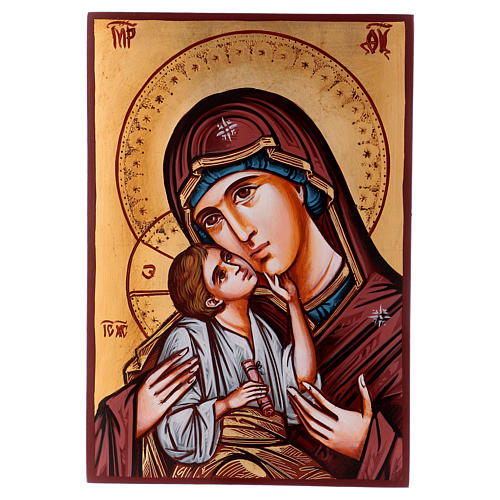

The incarnation, God taking on flesh, is venerated more in the Orthodox church than I have ever seen elsewhere. This has been a huge change for me because I always used to hate Christmas. I never understood the fanfare, when Easter was clearly the show-stopper. I think this is understandable in a protestant tradition, but it quickly became untenable once I re-found my Orthodox faith. You see, the Orthodox church does not celebrate the birth of Christ, as it were. It celebrates the mystery of Incarnation. It is a firm refutation to the worm-theologians of the Reformation, something that was a welcome reprieve to my soul,

and something I want to shout about from the rooftops. Flesh, matter, was the chosen instrument of God’s grace. The atoms of the earth, matter itself is something ‘very good,’ since God Himself has united it to His divine hypostases (the Greek for “person”). What happened at the Incarnation is a radical, ontological change in the fabric of the cosmos, and human nature is at the centre of it. God became man in order to save us. He did not abhor his body, or the embodiment we all experience, but lifted it up and mingled it with his divine nature so that the two come together perfectly. Since the Incarnation, we are lifted up to divinity by grace, being partakers of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4). For humankind, our fleshly nature is united to God in the mystery of the Incarnation. The Infant Jesus, born to a woman, accomplished that.

To return to the question that opened this blog, what does our posture towards children in Church communicate? In my church, the welcoming of children into the heart of worship communicates something profound.

It tells us that unlike the world, Christians revere childhood; they will inherit the kingdom of God. It makes clear that children can participate fully in the sacraments and the life of the church. And importantly, it communicates the tectonic shift that occurred when Jesus was born to a Virgin in a far-flung corner of the Roman Empire. God mingled with man in conception, birth and infancy, as much as He did in his salvific ministry.

“Whoever welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me.” (Mark 9:37). Now, with heart-bursting thanks to the Orthodox faith (and contrary to my Baptist friend) I thank God that Jesus was a baby.

Leave a comment